100 Years Ago, Drone Cameras Soared on Balloons

If you’re a photographer, one sure way to get ooohs and aaahs these days is to strap your camera to a drone and snap some pictures from the air. Photogs may think they’re at the cutting edge as they buzz a wedding with their mechanical whirly birds, but George R. Lawrence was taking DIY aerial photos long before it was cool — 100 years before it was cool.

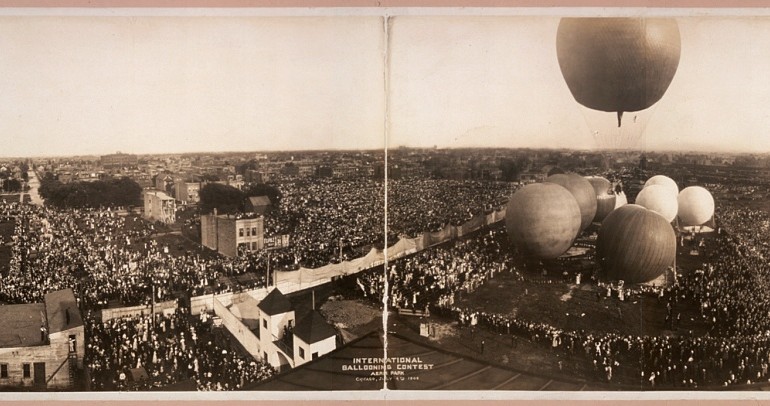

Lawrence was a Chicago photographer who pioneered the use of balloons, kites, and ladders to suspend his custom-made panoramic camera high above America’s cities, sports fields, and convention centers. At a time when the vast majority of people had never been in a particularly tall building, let alone airborne, his photographs offered a breathtaking new perspective. Accordingly, they got people’s attention. His photos were a marvel of their time, earning him fortune, accolades, and notoriety.

An eternal tinkerer, Lawrence made several mechanical innovations, eventually building his own camera and aerial rigs and ultimately ending up in pure aviation design. In the mid–1890s, he pioneered so-called flashlight photography, a predecessor to flashbulbs, and built a 1400-pound camera, the world’s largest at the time, to photograph the Alton Limited locomotive.

After becoming interested in aerial photography in 1901, his first experiment with a balloon was a disaster — he fell 200 feet to the ground (unharmed) when his platform detached from the balloon during his first assignment. After that, he decided to remain on the ground and send his camera aloft, creating a chain of between five and 17 kites to suspend his 49-pound panoramic camera, which he called the Captive Airship, as high as 2,000 feet above the ground. He used bamboo to stabilize the rig and piano wire to transmit the electrical signal that triggered the shutter. He would be granted nearly 100 patents for aviation-related devices over his lifetime.

What is perhaps his most famous photograph depicts a decimated San Francisco in the days after the massive 7.9 magnitude earthquake of April 16, 1906. The 160-degree vista was captured on a single 17-by-48-inch piece of film. The New York Times dubbed the quake and subsequent fire the first massively photographed disaster, but Lawrence’s photos were a cut (and 2,000 feet) above the rest; the iconic image was even recreated on the 100th anniversary. It would earn him a cool $15,000, and the interest of the military.

The elevated photos Lawrence took of landscapes, cities, military parades, presidential inaugurations, baseball games, and so on might not gain much attention today. Indeed, there are still photographers experimenting with cameras and kites. But his photos offer a truly unique perspective on the country at a time when cameras were cumbersome, rare, and almost exclusively ground-based.

Photos courtesy of the Library of Congress

via – Wired.com.